Some of history’s most victimized peoples are obliterated; others eventually achieve statehood. Why?

The Economist

Jun 20th 2015

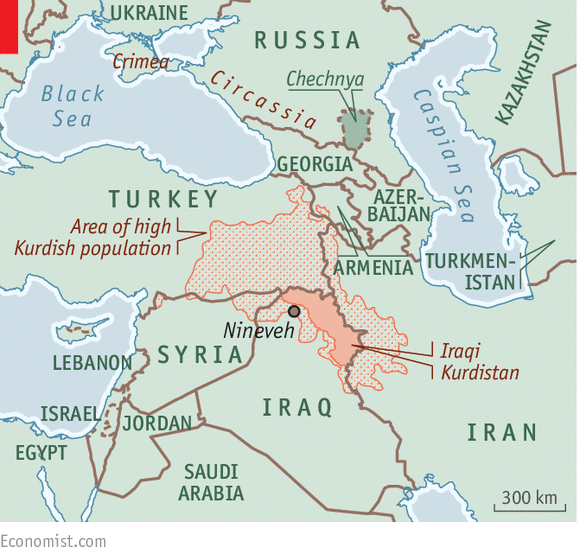

TWO peoples, both rooted in the tumultuous intersection of modern-day

Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Two peoples whose traumatic histories

overlap for generations—and then radically diverge. Both were

short-changed by the Ottoman empire’s collapse, and suffered in the

Arab-dominated countries carved out of it (see map). Yet one of these

perennial victims of Middle Eastern upheavals, the Kurds, may be set to

achieve its own state. The other, the Assyrians, or Syriacs,

Aramaic-speaking Christians whose ancient capital is Nineveh, is

politically marginalised, disinherited and now hounded by Islamic State.

“We dream of a place on Earth to call our own,” says Bassam Ishak of

the Syriac National Council of Syria.

TWO peoples, both rooted in the tumultuous intersection of modern-day

Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Two peoples whose traumatic histories

overlap for generations—and then radically diverge. Both were

short-changed by the Ottoman empire’s collapse, and suffered in the

Arab-dominated countries carved out of it (see map). Yet one of these

perennial victims of Middle Eastern upheavals, the Kurds, may be set to

achieve its own state. The other, the Assyrians, or Syriacs,

Aramaic-speaking Christians whose ancient capital is Nineveh, is

politically marginalised, disinherited and now hounded by Islamic State.

“We dream of a place on Earth to call our own,” says Bassam Ishak of

the Syriac National Council of Syria.

History’s combustions are unpredictable. A country for the

Kurds—which they will eventually get in northern Iraq if, or when, they

upgrade their current autonomous status to full sovereignty—seemed

unlikely for most of the 20th century. The dream of a Jewish homeland in

Palestine once looked at least as fanciful. History intervened. Yet,

amid its luck and chaos, there are reasons why the Kurds, like some

others, are set to make the leap from tragedy to sovereignty, while many

put-upon minorities do not. The pattern offers clues as to which

apparently benighted community might triumph next.

The most important factor, says Eugene Rogan, a historian at the

University of Oxford, is “critical mass”—whereby, despite being a

minority in a larger polity, a group forms a majority in a particular,

separable bit of it. That is the case for the Kurds in northern Iraq; it

is nowhere true of the Assyrians, whose greatest concentration, in

north-east Syria, has been dispersed by the civil war. Nor is it true,

for example, of the Crimean Tatars, resident for centuries in the

Crimean peninsula until their entire population was banished in one of

Stalin’s monstrous relocations.

It is useful if the minority have a long-standing, fairly legitimate

claim to the territory they inhabit. Physical geography can play a role:

some Iraqi Kurds speculate that their mountainous domain helped them

both to resist invaders and to safeguard their culture. How such places

were first subsumed by a bigger power matters, too

“You are likely to be swallowed whole,” Jean-Jacques Rousseau warned

the Poles before their lands were partitioned by Austria, Prussia and

Russia in 1772; “hence you must take care to ensure that you are not

digested.” Maintaining a national consciousness is part of that. But

administrative and legal details also count. Compare Armenia and

Chechnya. Slaughtered by the Ottomans during the first world war and

betrayed by the Western powers, as empires imploded around them

Armenians nevertheless managed to establish a short-lived state. It was

gobbled up by the Bolsheviks; but as Vicken Cheterian, an Armenian

commentator, says, because Armenia notionally entered the Soviet Union

as a state, it emerged as one in 1991. What had seemed a meaningless

internal border became an international one. By contrast the Chechens

were violently incorporated into Russia itself—and remain there, despite

two bloody separatist conflicts.

Bloodshed and suffering can wreck national aspirations. Consider the

Circassians, a stateless nation originating in the north Caucasus.

Hundreds of thousands of destitute Circassians died in 1864 as they fled

across the Black Sea from the tsar’s army, sometimes paying for their

passage with their children. Their boisterous weddings, ethos of

hospitality and codes of respect and honor are preserved in Turkey and

elsewhere; some still long for enhanced autonomy within Russia or even

independence. But, as Zeynel Besleney, an observer of Circassian

politics, notes, others resignedly concentrate on achieving minority

rights in their adopted homes.

Yet where suffering does not obliterate hopes of self-rule, it can

galvanise them. “Suffering creates a culture of messianism,” notes

Norman Davies, a historian, enabling nationalists to mobilise their

compatriots. It also helps to garner diplomatic support, essential for

groups seeking self-determination, says Johanna Green of the

Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, a network based in The

Hague. The Circassians and the Assyrians (subject, like the Armenians,

to massacres in 1915) would like their tragedies, too, to be regarded as

genocides. Ditto some Crimean Tatars (whose aim, now, is not

sovereignty but a more modest form of autonomy): the belief that the

deportation was a genocide should, says Arsen Zhumadilov of the Crimean

Institute for Strategic Studies, “be spread wide enough in the world so

that, when we are hurt today, the pain is felt everywhere.

And trauma can also bequeath another important asset: diasporas,

whose lobbying, broadcasting and fund-raising are ever more important.

Students of Zionism note wryly that, if it succeeded in attracting all

Jews to Israel, the state’s future would be jeopardized, because the

diaspora’s political and financial aid is vital. The benefits are

intellectual as well as practical. Barham Salih recalls how nationalist

ideas flourished among Kurds who, like him, fled Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Many—like Mr Salih, a former prime minister of the Kurdish regional

government—returned with valuable expertise. (Diasporas can also be

obstructively hardline: “In the diaspora you live the dream,” Mr Salih

says; “here you have to deal with reality.”)

None of these considerations matters unless, like Iraq—and the

Soviet, Austro-Hungarian, British and Ottoman empires before it—the host

regime crumbles, or more unusually, consents to a secession. But its

vassals must be equipped to exploit the crisis when it comes.

Critical mass; plausible borders; sympathy abroad; a story; a

diaspora; fragile overlords: where might these conditions next be met?

Russia, itself an internal empire, could yet disintegrate. So, under the

strain of democratization, might China, perhaps opening a path to

statehood for Tibet and the Uighurs, persecuted Muslims. Another

realignment of the Middle East seems inevitable. If Syria falls apart,

speculates Mr Ishak, the Assyrian, some of his scattered brethren might

come back. In the very long term, there is always hope.

The Economist

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Blog

Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Blog

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق